Implementation of norms to secure supply chains and encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities: Who needs to do what?

In dealing with a critical vulnerability, who is expected to do what in order to minimise security risks?

To answer this question, the international community fortunately has the framework we previously introduced. This framework helps us define the expectations for achieving cyber-stability. As mentioned earlier, the framework includes non-binding norms, among other elements, with two particular norms of special relevance for our discussion about ICT vulnerabilities and supply chain risks:

13i “States should take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain so that end users can have confidence in the security of ICT products. States should seek to prevent the proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions.”

13j “States should encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities and share associated information on available remedies to such vulnerabilities to limit and possibly eliminate potential threats to ICTs and ICT-dependent infrastructure.”

However, these norms are by default abstract and general in scope – and voluntary in nature. Who should read them – and how?

Unpacking the two norms: What did States specifically agree about, and do other stakeholders concur?

While not legally binding, both norms are seen as a collective understanding confirmed by all UN Member States on how to ensure a safer digital landscape. In 2021, States confirmed the eleven cyber norms, as part of the cyber-stability framework, and agreed upon the implementation points for each of them. However, a deeper contemplation of concrete suggestions and steps opens numerous questions.

In particular, when discussing norm 13i (related to supply chain security), States the broad measures such as putting in place, at the national level, transparent and impartial frameworks and mechanisms for supply chain risk management to more narrowly define ones, (e.g. putting in place measures that prohibit the introduction of harmful hidden functions and the exploitation of vulnerabilities in ICT products). The 2021 UN GGE report clarifies that States are primary responsible actors for implementing this norm. However, at the same time, states agreed that the private sector and civil society should assume a relevant role in the process. What can be concrete responsibilities for these stakeholders? The norm does not clarify this issue further.

With regard to norm 13j (related to responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities), the language remains less detailed and specific. The norm promotes a necessity for ‘timely discovery and responsible disclosure and reporting of ICT vulnerabilities’. The norm also mentions that states could consider developing impartial legal frameworks, policies, and programmes on vulnerability handling; develop guidance and incentives, and protect researchers and penetration testers. These measures would find broad support across cybersecurity experts, users, and other stakeholders; however, details are critical – what do ‘impartial legal frameworks’ mean? How will states protect researchers and penetration testers? And what would ‘responsible reporting’ entail? To whom should vulnerabilities be reported to ensure responsible reporting? The norm does not clarify this either.

Discussions with the Geneva Dialogue experts have highlighted that these questions are just as important and on the minds of stakeholders. They have raised additional concerns, such as how to tackle the current geopolitical challenges arising from technological competition between countries and the different rules and regulations in this field. These challenges and risks of conflicting rules and laws in this field across countries can present hurdles for researchers and industry players trying to collaborate across borders to put these norms into action.

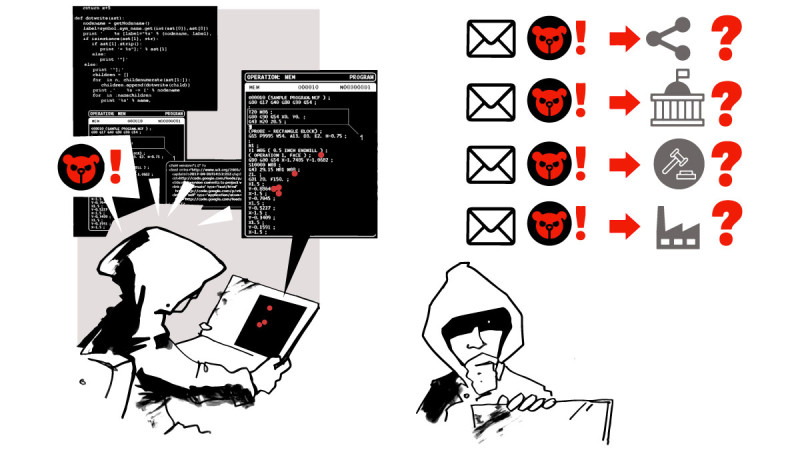

The role of governments in the implementation of these norms raised another concern, especially in regards to the states who have advanced cyber capabilities to stockpile vulnerabilities for their cyber offensive and defensive programs. How to build trust between relevant non-state stakeholders and governments to implement these norms and encourage responsible vulnerability disclosure? How to facilitate information exchange to implement these norms between states and relevant non-state stakeholders, as well as between different states?

The Geneva Dialogue experts have also expressed concerns about the implementation of the norm 13i on supply chain security. In particular, it has been noted that the ICT supply chains now involve multiple stakeholders, and that no single entity has complete control over them. The complexity of these supply chains, with various participants and cross-border data flows, makes achieving optimal security challenging. Each organisation makes security decisions based on its resources and capabilities, which may not align with the security needs of others. The absence of universally accepted methods for conducting evidence-based security assessments in supply chain security poses challenges for organisations of different sizes. They must make security choices and decide which digital products and suppliers can be trusted. All these decisions often have an immediate impact on the security of customers and users. In this context, the Geneva Dialogue experts stressed the need for globally accepted rules and standards for supply chain security, promoting security by design and default in digital products. However, is it possible to develop such rules today, and is there an appropriate international platform for facilitating these discussions?

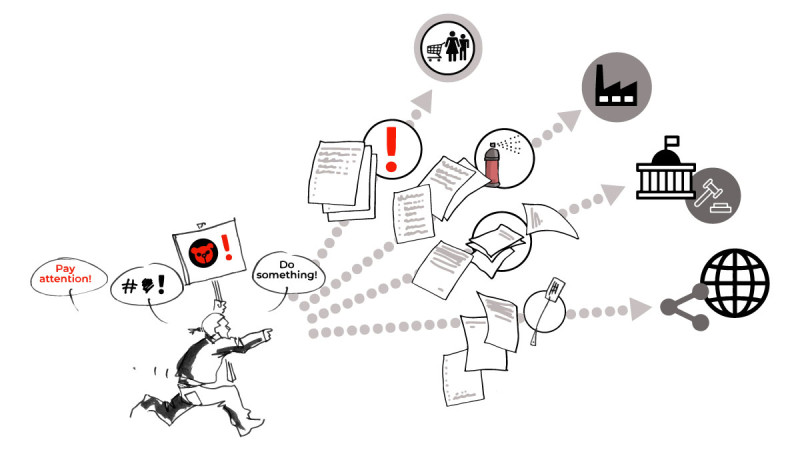

While norms set expectations, translating them into practical actions is of the essence. The Geneva Dialogue experts supported translating the norms as non-binding diplomatic agreements into more tangible processes, policies, and regulations. The key questions are how to develop such policies and regulations, and where to establish them. What should be the fundamental principles guiding the creation of such policies and regulations to effectively implement the essence of the norms?

With many open questions, the consultations with the Geneva Dialogue experts showed that relevant non-state stakeholders support the norms negotiated by states: if properly implemented, they can help significantly increase the security and stability in cyberspace. But the ‘devil is in the details’ and the key caveats are about ‘if’ and ‘properly implemented’ – what would this mean in practice?

With the Geneva Manual, we launch a global conversation on how the norms implementation for the security of cyberspace can become a reality or, where it is already a reality, what can be improved. Based on the idea that achieving effective cybersecurity requires continuous cooperation and commitment from all involved parties, we have outlined suggestions as to ‘who should do what.’ With the help of our story (inspired by real events), we explore different roles within various stakeholder groups and delve into what each role can include, and could contribute to. This involves understanding the expectations, motivations, incentives, and challenges faced by these groups. Through the regular discussions with the Geneva Dialogue experts, we also discovered some good practices that can inspire others in the international community to play their part in promoting cyber-stability.

Implementation of the two norms: Roles and responsibilities to achieve cyber-stability

We often say that cybersecurity is a team effort, but how can we ensure that such a ‘team’ works together effectively? To address this, we collected the views of the Geneva Dialogue experts: these multistakeholder inputs helped us analyse where roles start and end, which drivers are needed to incentivise responsible behaviour across relevant non-state stakeholders, and which challenges remain unsolved, therefore requiring further attention of the international community.

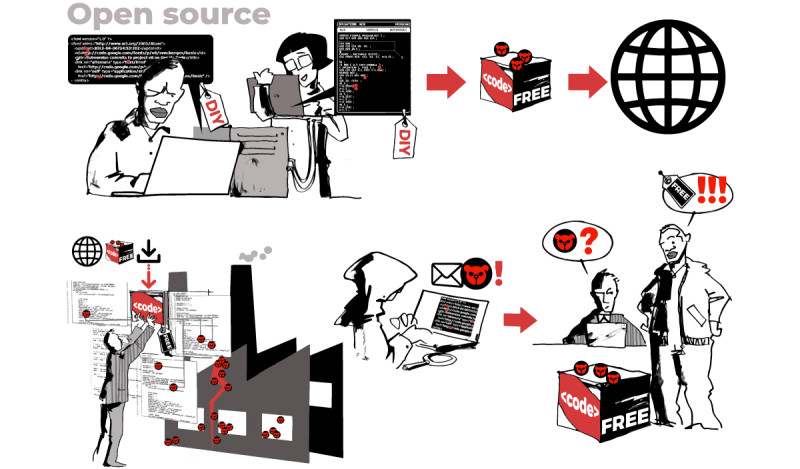

If you were the owner of an open-source tool where the vulnerability had been discovered, what actions would you take to minimise the security risks? What difficulties may you encounter in taking such actions?

As a customer and user of digital products, what would you expect from your suppliers? What would motivate you to keep trusting them?

Do researchers – when discovering the vulnerability – always have to coordinate actions with vendors? Authorities? To whom would the reporting of vulnerabilities be considered as ‘responsible’ following the norm 13j?

Can (and should?) cybersecurity researchers independently mitigate the exploitation of the vulnerability without notifying the manufacturer? Or national authorities?

It is important to note that the Geneva Dialogue experts have recognised that each of the listed stakeholders has many sub-groups that might have additional specific roles and responsibilities. For instance, manufacturers include producers of software and hardware, as well as service operators of the cloud or telecommunication infrastructure, while civil society includes advocacy groups, grassroot organisations, think-tank and educational institutions. In addition, there may be a need to elaborate on roles of responsibilities of additional stakeholder groups, such as the standardisation community. Such discussion may be part of the future work of the Geneva Dialogue, towards the next edition of the Geneva Manual.

Separately, the Geneva Dialogue experts have discussed expectations from states and regional organisations and highlighted their role in coordinating efforts with other states to ensure the ICT supply chain security (given ICT supply chains are global and cross-border) as well as in addressing security issues in digital products with efficient legal framework and policies:

- Codifying the norms and promoting responsible behaviour norms should be translated into clear regulatory expectations, though this can be very challenging given the complex nature of ICT supply chains. The clear interoperable security criteria for testing and security assessments are needed to address both technical and political concerns these days

- However, even if such regulatory frameworks emerge, the challenge is to ensure the adoption of cybersecurity recommendations across organisations, especially across small and medium companies. While guidelines may be published to mitigate supply chain vulnerabilities and reduce risks, it remains unclear how to ensure that organisations actually follow these recommendations

- In the context of OSS, government bodies could step in coordinating efforts between manufacturers, open-source community, and other relevant parties, sharing information, and leveraging international collaborations to address cybersecurity threats and support their respective countries in times of crisis

- The national governments’ ability to communicate and collaborate with other states is considered crucial in effectively addressing cybersecurity challenges, as well

- States are also expected to encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities, recognise their exploitation as a threat, increase transparency about stockpiling of ICT vulnerabilities (such as through vulnerability equities processes, VEP), and limit commercial exploitation of ICT vulnerabilities 16OSCE Confidence-building measure (CBMs) on #16: “Participating States will, on a voluntary basis, encourage responsible reporting of vulnerabilities affecting the security of and in the use of ICTs and share associated information on available remedies to such vulnerabilities, including with relevant segments of the ICT business and industry, with the goal of increasing co-operation and transparency within the OSCE region. OSCE participating States agree that such information exchange, when occurring between States, should use appropriately authorized and protected communication channels, including the contact points designated in line with CBM 8 of Permanent Council Decision No. 1106, with a view to avoiding duplication”. – https://dig.watch/resource/confidence-building-measures-reduce-risks-conflict-stremming-ict

GCSC Norm #3 to Avoid Tampering: “[…] the norm prohibits tampering with a product or service line, which puts the stability of cyberspace at risk. This norm would not prohibit targeted state action that poses little risk to the overall stability of cyberspace; for example, the targeted interception and tampering of a limited number of end-user devices in order to facilitate military espionage or criminal investigations.” – https://hcss.nl/gcsc-norms/

Leave A Comment