1Context: What is the Geneva Manual?

In 2004, beginning with the first United Nations Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on information and communications technology (ICTs), states started debating how to behave in cyberspace. Much has happened since. States agreed that international law applies in cyberspace and have agreed to eleven norms for responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. Meanwhile, outside the UN system, states and regional organisations have developed their own rules and have published numerous confidence building measures (CBMs), as listed in the IGF BPF report. This demonstrates that states indeed see cyberspace as an important asset and, furthermore, a place that should remain peaceful.

However, the ICT infrastructure that makes the internet such a unique and valuable place is neither owned or operated by states, nor do states have the sole ability to govern it, due to its transnational nature. In fact, most of the ICT infrastructure is owned and operated by thousands of private companies, which also produce the devices, from traditional computers to medical devices, connecting to, and utilising the internet. In addition, technical community sets the standards and has the hands-on knowledge and expertise on running and securing the ICT environment, while civil society, with its broad understanding of social and economic context, wide networks, and ability to reach out to end-users, plays and can play an important role to enhance citizens’ awareness and advocate for their safety and rights.

These stakeholders are often only spectators to the normative processes by states, yet, in the end, play an important role for the implementation of these diplomatic agreements.

Meanwhile, digital products are ubiquitous and underpin the functioning of modern society. The fact that they can be vulnerable means they can be abused by other actors for malicious purposes. This raises security concerns at various levels – from the security of particular users, to matters of international peace and security. States carry primary responsibility for security of its citizens and infrastructure; however, this responsibility is not absolute, as it is clear that they cannot meet these expectations about cyberspace without engaging with other actors: a cooperation between states, private sector, academia, civil society, and technical community is required to ensure an open, secure, accessible, and peaceful cyberspace.

Norms of responsible behaviour in cyberspace, adopted within the UN and which are further discussed in the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG), give common guidance to what states are expected to do to ensure stability of cyberspace, including the security of digital products. But what are these other actors expected to do to support the implementation of those norms? Where and how can they support states in ensuring the security and stability of cyberspace, along with promoting responsible behaviour in it? What challenges may they face along the way, and how to address them through dialogue with states and other stakeholders?

The Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace (Geneva Dialogue) was established by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs and led by DiploFoundation with the support of the Republic and State of Geneva, Center for Digital Trust (C4DT) at EPFL, Swisscom, and UBS to analyse the roles and responsibilities of various actors in ensuring the security and stability of cyberspace. In this context, the Geneva Dialogue stems from the principle of ‘shared responsibility’ and particularly asks how the norms might be best operationalised (or implemented) by relevant actors as a means to contribute to international security and peace.

Concretely, the Dialogue investigates the consequences of agreed upon norms for relevant non-state stakeholders from the private sector, academia, civil society, and technical community, and tries to clarify their roles and responsibilities. It does not aim to find consensus, but to document agreement or disagreement on the roles and responsibilities as well as concrete steps each stakeholder could take, and the relevant good practices as examples. For this, the Dialogue has invited over 50 experts and representatives of stakeholders around the world (further referred to as Geneva Dialogue experts throughout the document) to discuss their roles and responsibilities, and the implementation of cyber norms in this context. The results – published in the form of the Geneva Manual – offer possible guidance for the international community in advancing the implementation of the existing norms and establishing good practices. The Geneva Manual also reflects the diverse views of relevant non-state stakeholders and outlines some of the open questions to which the Dialogue has yet to provide answers, but which are important for a better understanding of challenges by states.

The inaugural edition of the Geneva Manual focuses on the two norms related to the supply chain security and responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities. In the coming years, the Dialogue will continue discussing the implementation of other norms to expand the Geneva Manual. In section 2, we explain our approach and share more information about the particular norms we focus on.

We invite all interested stakeholders to join us on this path to collect ideas, core challenges, opportunities, and good practices for relevant non-state stakeholders to implement the existing norms, and collectively help make cyberspace more secure and stable. The Geneva Manual remains open to comments and suggestions at genevadialogue.ch, and will be continuously updated to reflect the changes driven by the rapid development of technologies.

2Main concepts

Before we discuss the implementation of norms in cyberspace, let us introduce some of the concepts and terms which will be used throughout the Geneva Manual.

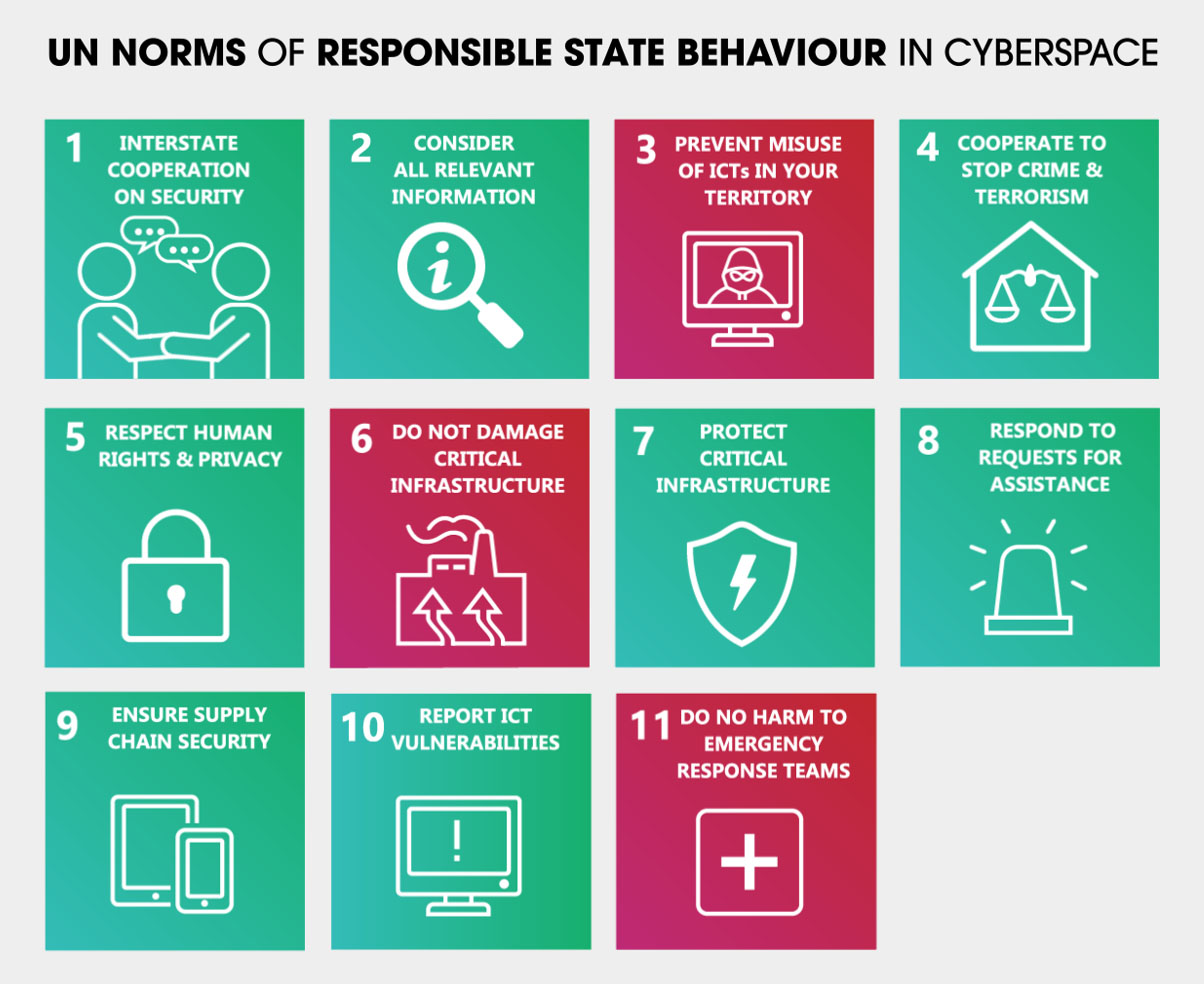

First, we should clarify what the ‘norms of responsible behaviour in cyberspace’ are. These norms are a part of the UN cyber-stability framework, created by the UN GGE 1UNGGE 2013, 2015 and 2021 reports provide the basis for the UN cyber-stability framework. (mentioned earlier), and later endorsed by all UN Member States to encourage responsible conduct among nations in cyberspace. Besides the non-binding eleven cyber norms, the framework includes three foundational pillars: binding international law; various confidence-building measures, particularly those to strengthen transparency, predictability and stability; and capacity building.

The framework, agreed upon by states, focuses on regulating state conduct in cyberspace. While it acknowledges the role of various stakeholders, it provides limited guidance on their roles and responsibilities, leaving room for ambiguity regarding their expected actions as well as further work to unpack the norms into coherent practices and actions.

These various relevant non-state stakeholders include representatives of the private sector and industry, academia, technical community, and civil society.

Despite the voluntary nature of the eleven norms, they are foundational as a part of the framework encouraging states to reduce the risk of cyber conflicts, and promoting stability and cooperation in cyberspace.

UN cyber norms, ASPI

Given that the norms and framework do not extensively cover the roles and responsibilities of relevant non-state stakeholders, the Geneva Manual aims to bridge this gap by focusing on how such actors can implement cyber norms, as a step to further enhance stability and security in cyberspace.

The inaugural edition of the Geneva Manual begins with two norms concerning supply chain security (#9) and responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities (#10). These norms follow the Geneva Dialogue’s previous discussions on digital product security and the roles industry and various actors play in ensuring it.

Unpacking these two norms and expectations from relevant non-state stakeholders, the Geneva Manual introduces more specific roles (for example, manufacturers of digital products, code owners, vendors, researchers, etc.). The Geneva Manual uses the term ‘digital products’ and understands them as software, hardware, or their combination, and such products are characterised by (i) containing code; (ii) ability to process data; or (iii) ability to communicate/interconnect. Though they are not necessarily synonyms, for simplicity, the terms ‘digital products’ and ‘ICTs’ are used interchangeably in the Geneva Manual.

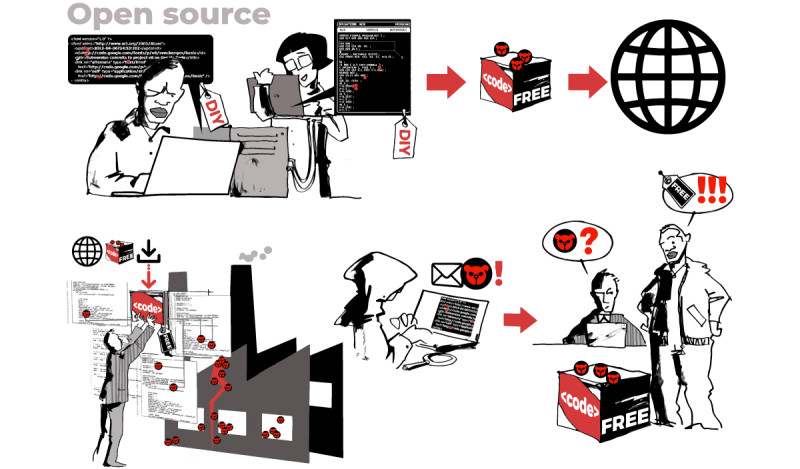

In this context, manufacturers, vendors, or service providers include a company or an entity that produces or provides digital products and services, or ICTs. A code owner can be a vendor and a manufacturer in cases where they are responsible for developing and maintaining software code embedded in a final digital product; a particular group of code owners are those engaged with producing the open source software (OSS). Researchers include individuals or organisations who discover vulnerabilities or any other security flaws in digital products with the intention to minimise the security risks for users of such products.

Vulnerability disclosure is an overarching term which the Geneva Manual uses to describe the process of sharing vulnerability information between relevant non-state stakeholders. Vulnerability disclosure can be coordinated (CVD) in cases where several parties need to exchange information in order to mitigate the vulnerability and reduce security risks. 2Security of digital products and services: Reducing vulnerabilities and secure design. Industry good practices. Geneva Dialogue report, 2020. https://genevadialogue.ch/wp-content/uploads/Geneva-Dialogue-Industry-Good-Practices-Dec2020.pdf ICT vulnerability, or vulnerability in digital products, implies a weakness or flaw in such products that can potentially be exploited by malicious actors to get unauthorised access to ICT system or infrastructure, and/or lead to unintended system failures.

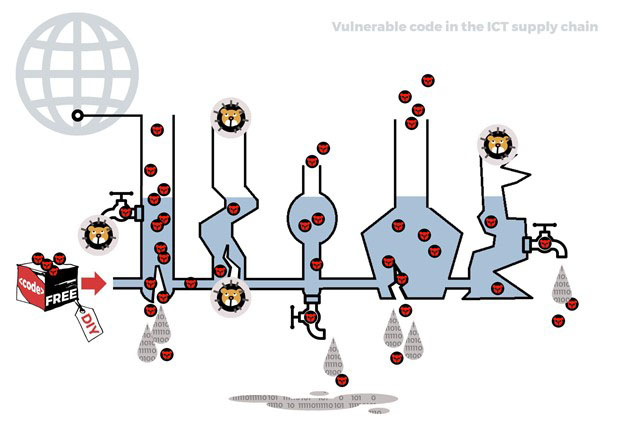

Manufacturers and their suppliers form the core of a complex network of ICT supply chains that encompasses various components and products, and involves multiple stages and stakeholders, from the initial design and manufacturing of digital products to their distribution, installation, maintenance, and eventual disposal and recycling. The primary goal of ICT supply chains is to ensure the efficient production, delivery, and support of digital products/ICTs to meet the demands of customers and end users. ICT supply chains, however, bring about a complex web of interdependencies of digital products, and thus also allow for vulnerabilities in some to penetrate throughout the supply chain rendering it insecure.

Organisational customers of digital products include the entities who procure, purchase, and use digital products in their day-to-day operations, as well as provide further digital or non-digital services to other consumers or end-users. Such customers include various organisations of different sizes, with different resources and cybersecurity knowledge to address cyber threats. However, organisational customers should be perceived differently from citizen customers of digital products (i.e. end-users), who refer to individuals who use digital products and normally do not have any cybersecurity knowledge to address cyberthreats. Civil society refers to a broad set of non-government organisations including associations representing the interests of end-users, but also the advocacy groups, grassroot organisations, think-thanks, training and awareness raising organisations, and alike.

3Introduction: Addressing norms related to supply chain security and responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities

3.1 The challenge: How to address insecure digital products and enhance cyber-stability?

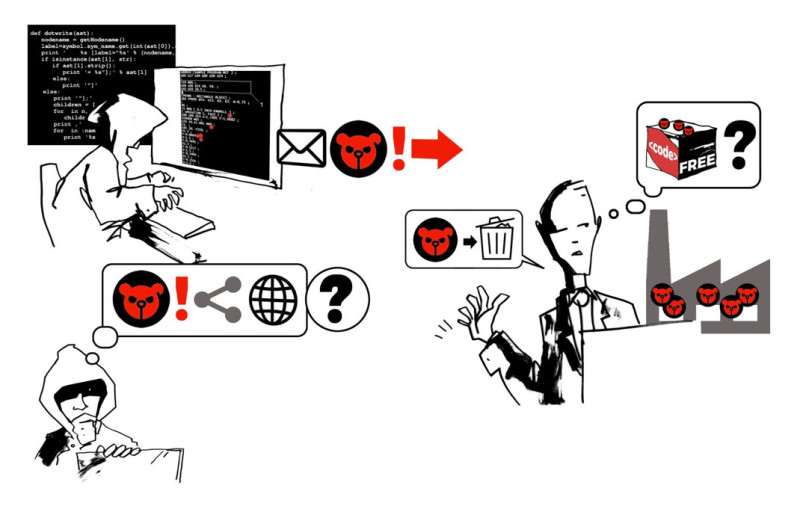

Once upon a time, a security researcher (i.e. ‘white hat hacker’) known as @DinaSyn29 discovered a critical vulnerability – which it dubbed ‘TeddyBear’ – in a Windows desktop client of an instant messaging and VoIP social media platform Networkarium. This vulnerability could allow an attacker to remotely take over a user’s system simply by sending a malicious message, and then run a malicious code on it.

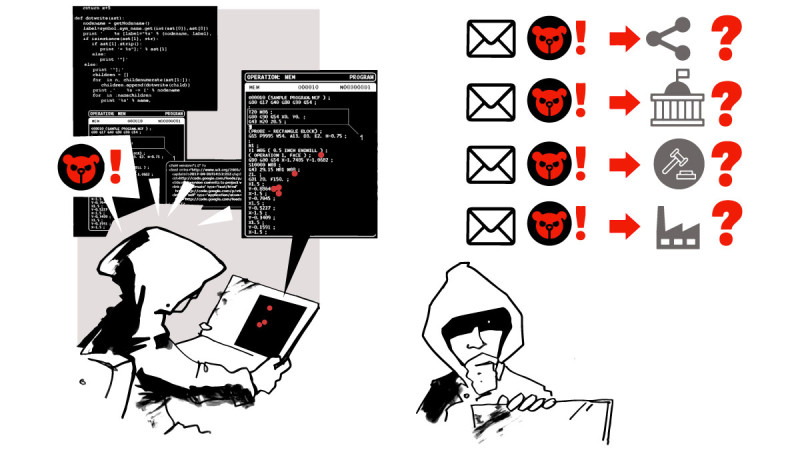

The researcher, following responsible disclosure practices, reported the ‘TeddyBear’ vulnerability to the Networkarium security team and provided detailed information about the exploit. However, Networkarium initially downplayed the severity of the issue, leading to a disagreement between @DinaSyn29 and the company.

Networkarium argued that the impact of the vulnerability was limited because it required user interaction, such as clicking on a link or opening a message, to be exploited. On the other hand, @DinaSyn29 insisted that the potential for abuse was significant – not least due to general lack of awareness of ordinary users not to open suspicious messages – and that immediate action was necessary to protect users.

In the meantime, the analysis by the Networkarium security team revealed that the vulnerability was ‘imported’ from a third-party code (a RunTix library), which Networkarium developers embedded into the app’s code.The RunTix library containing the discovered vulnerability is part of an open-source project, developed voluntarily by a programmer known as AutumnFlower, which she made available for wider use by anyone for free. The company’s security team encountered challenges in developing a patch, as AutumnFlower responded slowly and without much interest, despite acknowledging the vulnerability report disclosed by the Networkarium team.

As the disagreement persisted, @DinaSyn29 was frustrated by what she perceived as the Networkarium’s lack of urgency and decided to publicly disclose the vulnerability for everyone to see – complete with proof-of-concept code which would allow anyone to test exploiting the vulnerability – before Networkarium had a chance to release a fix.

What should be the next steps for Networkarium to respond to this and mitigate the security risks for its users? What should have been done by Networkarium to allow a transparent and responsible vulnerability disclosure process? What lessons-learned can be made here for Networkarium? What should be the next steps for the OSS maintainer to do in this context? What lessons-learned can be made for the open-source community to ensure agility in patching the vulnerable code? What could the researcher have done differently when Networkarium downplayed the relevance of the vulnerability, instead of publicly disclosing it?

Several months ago, a civil society organisation named CyberRights International published an investigation about a surveillance operation on journalists in several countries – malicious actors targeted victims to get access to their mobile phones and stole confidential information like sensitive chats, protected sources, etc. The operation exploited the ‘TeddyBear’ vulnerability in the Networkarium messaging platform mentioned earlier. In this investigation, CyberRights International teamed up with a cybersecurity company CyberSecurITatus and revealed that a skilled and sophisticated actor – known as APT102, often assumed to be sponsored by the state of Absurdinia – is behind the operation.

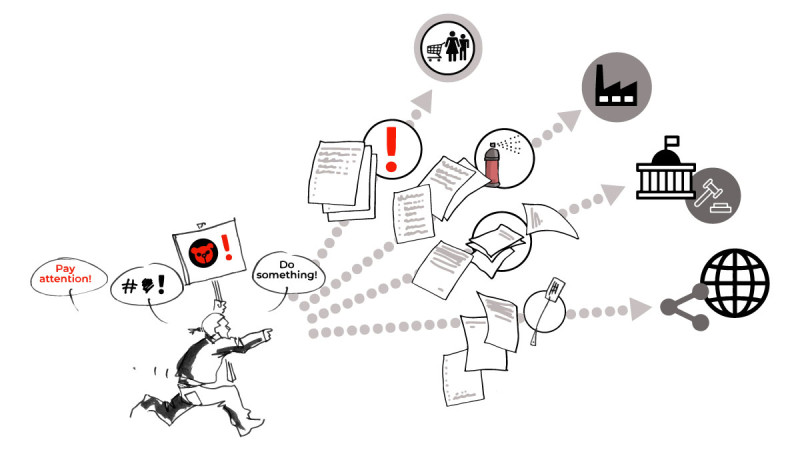

Understanding the gravity of the situation, CyberRights International publicly shamed Networkarium for a failure to ensure the security for users, as well as Absurdinia for targeting journalists and posing threat to user privacy and freedom of expression. Global media have widely reported about the case.

The investigation by CyberSecurITatus revealed that attackers used the ‘TeddyBear’ vulnerability to also breach networks of a much larger company Important Systems Inc. (InSys), which produces hardware and software solutions typically used by energy power plants and industrial facilities. InSys used the messaging platform for internal communications, which allowed the attackers to infect their desktops, and attempt to enter their corporate network. The cybersecurity experts of CyberSecurITatus reported the failed supply chain attack, where attackers tried to compromise the networks of InSys but didn’t have much success due to the properly segmented configuration of their internal IT network.

What should be the next steps for Networkarium to respond to this investigation? What can CyberRights International do to promote security for users? What should be the next steps for InSys to respond to this investigation, ensure the security of its products in accordance with the existing UN cyber norms (13i and 13j)?

The NCA – national cybersecurity authority of Utopistan, a country where Networkarium was legally established, became aware of CyberRights International’s investigation and the harm caused by Networkarium’s insecure service to citizens in the country and worldwide.

In response, the authority initiated its own investigation into Networkarium’s security practices. It was revealed that Networkarium failed to notify both the authority and affected users within 72 hours of discovering the vulnerability, and did not report the unpatched vulnerability to the authority.

What should Networkarium respond to this? What are your thoughts on the decisions made by the national authority?

The story above emphasises that cyberattacks, resulting in security and safety risks for users and causing societal and economic disruptions, most often stem from exploiting vulnerabilities in digital products and a lack of transparency in complex ICT supply chains, which delays the identification of relevant actors responsible for the mitigation of such vulnerabilities. The lack of security in digital products also allows well-resourced threat actors and such attacks to damage global cyber-stability.

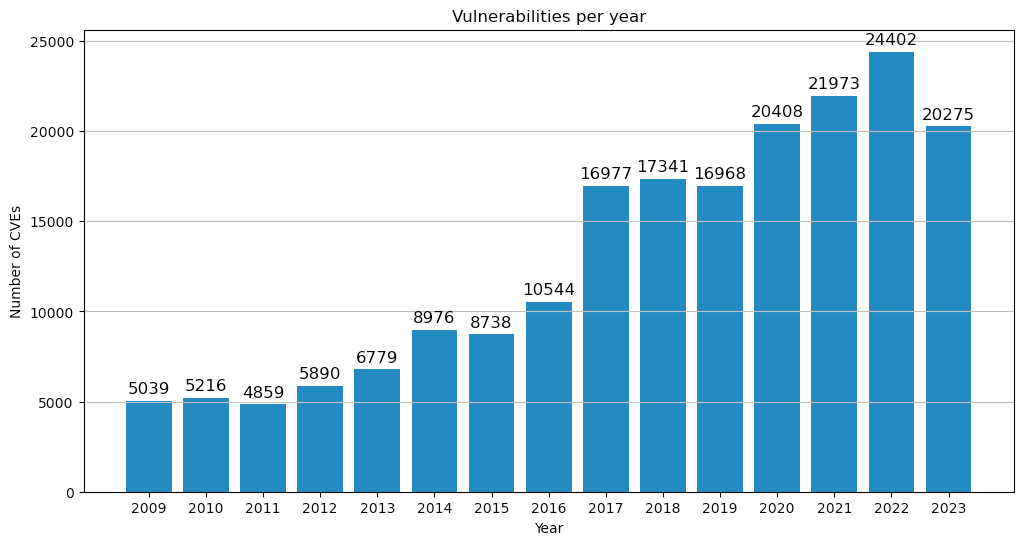

“In 2022, malicious cyber actors exploited older software vulnerabilities more frequently than recently disclosed vulnerabilities and targeted unpatched, internet-facing systems.” 3Joint Cybersecurity Advisory (CSA) issues by the NCSC, the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the US National Security Agency (NSA), the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS), the Computer Emergency Response Team New Zealand (CERT NZ) and the New Zealand National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-NZ), 2022. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-215a

Number of published vulnerabilities per year (CVEs) worldwide (CVE.org)

It should be noted that not all vulnerabilities in digital products necessarily pose a significant threat. The severity of a vulnerability depends on various factors, including the nature of the vulnerability, the context in which the product is used, and the potential impact of exploitation. Additionally, network misconfigurations, characterised by errors or oversights in the configuration and management of network devices, systems, and applications, have been identified as a prevalent source of systemic weaknesses. These misconfigurations can introduce security vulnerabilities, providing opportunities for unauthorised access or other malicious activities, even in organisations that have attained a higher level of cyber maturity.

In order to address this problem, several international processes formulated the cyber norms of responsible behaviour in cyberspace to reduce ICT vulnerabilities and, therefore, security risks for users. For instance, the UN cyber norms, which have been agreed on and endorsed by all UN Member States. These include the UN GGE norm 13(i) and 13(j) related to the integrity of the supply chain and security of digital products, and the responsible reporting of vulnerabilities and the related information sharing respectively. These norms, along with others from different regional and multistakeholder forums, call for close cooperation between states and relevant non-state stakeholders.

One of the key challenges, however, lies in the implementation of such norms.

The environment in which this cooperation should take place is incredibly complex and uncertain: the threats in cyberspace are heavily influenced by geopolitics; emerging national legal and regulatory frameworks are pressed by national security concerns, and risk additional fragmenting of the global policy environment; traditional existing practices, such as certifications, may not entirely address the need for greater security and safety in the use of ICTs, nor may they be suitable for the various stakeholders, convergence of technologies, and the pace at which the threat landscape changes.

Moreover, the agreed non-binding cyber norms for responsible behaviour are often unfamiliar to relevant non-state stakeholders, or lack the specificity needed to offer practical guidance for their implementation by them. What’s more, the norms are designed to primarily support political and diplomatic engagement and therefore may not provide the clear technical and practical guidance required by relevant non-state stakeholders. The current situation is also complicated by the existing limitations that hinder such stakeholders from actively participating and making meaningful contributions to international processes. These processes predominantly centre around the behaviour of states as the primary subjects of international law. Consequently, these limitations restrict opportunities for stakeholders to gain a comprehensive understanding of the present challenges, exchange their own best practices, and benefit from shared experiences in advancing responsible behaviour in cyberspace.

Therefore, in order for the relevant non-state stakeholders – the private sector, academia, civil society, and technical community – to effectively support the implementation of existing norms and contribute to cyber-stability, it is crucial to clarify their needs, roles, and responsibilities. Besides, there is a need to discuss how to approach those stakeholders who are not interested, unaware or unwilling, to cooperate in enhancing responsible behaviour in cyberspace. Focusing on such actors, the Geneva Dialogue sees as its mission to support such stakeholders involved in global discussions about responsible behaviour in cyberspace, securing digital products and ICT supply chains, and reducing risks from ICT vulnerabilities.

3.2 Approach: How does the Geneva Dialogue address the implementation of norms?

The Geneva Dialogue on Responsible Behaviour in Cyberspace (Geneva Dialogue) is an international process established in 2018 to address the challenge described above and, in particular, map the roles and responsibilities of actors, thus contributing to greater security and stability in cyberspace. It is led by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) and implemented by DiploFoundation, with support of the Republic and State of Geneva, Center for Digital Trust (C4DT) at EPFL, Swisscom and UBS.

Asking how the norms 4First and foremost, non-binding voluntary UN GGE norms (as agreed by States and endorsed by the UN membership in 2021) are meant here: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/075/86/PDF/N2107586.pdf?OpenElement. Further in the text, norms and ‘cyber’ norms are used interchangeably to refer to the UN GGE normative framework. might best be operationalised (or implemented) as a means to contribute to international security and stability, and stemming from the principle of ‘shared responsibility 5It is clear that states cannot implement agreements made within the UN GGE as well as 2021 UN OEWG report alone, and thus cannot meet their responsibilities without engaging with other actors, while vice versa is applied to other actors and to their responsibilities in cyberspace. for an open, secure, stable, accessible, and peaceful cyberspace, the Geneva Dialogue has first focused on the role of the private sector who often owns and/or maintains digital products and ICT systems. After rounds of regular discussions with industry partners, the Geneva Dialogue produced an output report with good practices for reducing vulnerabilities and secure design (November 2020).

Later, the Geneva Dialogue focused on governments’ approaches and policies to regulate the security of digital products and covered other actors (such as standardisation and certification bodies) in this regard, to ask a fundamental question on how fragmentation in cybersecurity efforts could be decreased for greater security in cyberspace. For that purpose, the Geneva Dialogue published the policy research, prepared by the Center of Security Studies at ETH Zürich, which analysed various governance approaches to the security of digital products (November 2021).

All of these efforts laid the foundation for clarifying the roles and responsibilities of relevant non-state stakeholders in implementing cyber norms. The results are published in the Geneva Manual, focusing initially on the two norms concerning responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities and supply chain security, to ensure the consistency with the previous work. The Geneva Dialogue will expand its efforts to explore the implementation of other cyber norms in the coming years.

The UN cyber-stability framework, mentioned earlier, negotiated and agreed upon by UN Member States, provides a solid basis for the Geneva Manual: the norms guide on expected outcome in efforts to enhance stability and security in cyberspace. While these UN cyber norms are currently the one and only norms package endorsed by the entire UN Membership, the Geneva Dialogue explored other relevant normative frameworks to build connections, where possible, and avoid duplicative efforts. These normative frameworks include the examples provided by the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG), intergovernmental organisations (such as OSCE, OECD, ASEAN, OAS), and multistakeholder initiatives (such as the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace, Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace, IGF Best Practice Forum on Cybersecurity, and many others).

The Geneva Manual covers different aspects of the two norms, such as who should be involved, what they should do, and why it matters. It also addresses the challenges and good practices for putting these norms into action. To gather this information, the Geneva Dialogue conducted regular virtual consultations and side-event discussions between April and November 2023. These discussions involved more than 50 representatives from various stakeholder groups, including the private sector, academia, civil society, and technical community. The findings consist of diverse stakeholder perspectives, good practices, as well as identified challenges in enhancing the security of ICT supply chains and reducing ICT vulnerabilities, thus implementing these cyber norms.

To this end, the Geneva Manual, alongside all previous analytical work produced by the Geneva Dialogue, is a consolidation of multistakeholder and geographically diverse views and opinions by experts, as well as institutions invited by the Swiss FDFA and DiploFoundation.

3.3 The value: Who should read the Geneva Manual and how to use it?

As part of the Swiss Digital Foreign Policy Strategy 2021-24, the Geneva Dialogue pursues its mission – to assist relevant non-state stakeholders who are interested to participate and contribute to global discussions on responsible behaviour in cyberspace and the implementation of relevant norms in this regard. These stakeholders include decision-makers in various organisations representing the private sector, academia, civil society, and technical community, who are interested to help enhance the security of digital products and ICT supply chains, and minimise risks associated with ICT vulnerabilities.

For this purpose, the Geneva Manual as a tangible outcome of the Dialogue, focuses on:

- empowering such stakeholders to help them understand their roles and responsibilities, and contribute, in a meaningful way, to processes where the international community discusses how we behave in cyberspace, use and secure digital products and technology, secure supply chains, and make the digital world safer

- sharing good practices from different communities and regions to inspire others to follow suit, leading to a safer and more secure digital environment

- raising awareness about the importance of international cyber processes to sensitise stakeholders to play a bigger role in such processes

The Geneva Manual emphasises that it is not just implementing norms which is important, but rather proactively taking actions which enhance cybersecurity and stability in cyberspace, particularly by reducing ICT vulnerabilities in digital products and minimising supply chain risks.

The Geneva Manual, therefore, offers an action-oriented approach to cyber-stability: through the story introduced at the beginning, it explores the roles (Who), responsibilities and actions (What), incentives (Why), and challenges. We also connect actions to norms: in sharing stakeholders’ interpretations of norms and drawing a direct line between practical actions and diplomatic arrangements, the Geneva Manual thus facilitates the understanding of the UN cyber-stability framework and its effective implementation.

4Implementation of norms to secure supply chains and encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities: Who needs to do what?

In dealing with a critical vulnerability, who is expected to do what in order to minimise security risks?

To answer this question, the international community fortunately has the framework we previously introduced. This framework helps us define the expectations for achieving cyber-stability. As mentioned earlier, the framework includes non-binding norms, among other elements, with two particular norms of special relevance for our discussion about ICT vulnerabilities and supply chain risks:

13i “States should take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain so that end users can have confidence in the security of ICT products. States should seek to prevent the proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions.”

13j “States should encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities and share associated information on available remedies to such vulnerabilities to limit and possibly eliminate potential threats to ICTs and ICT-dependent infrastructure.”

However, these norms are by default abstract and general in scope – and voluntary in nature. Who should read them – and how?

4.1 Unpacking the two norms: What did States specifically agree about, and do other stakeholders concur?

While not legally binding, both norms are seen as a collective understanding confirmed by all UN Member States on how to ensure a safer digital landscape. In 2021, States confirmed the eleven cyber norms, as part of the cyber-stability framework, and agreed upon the implementation points for each of them. However, a deeper contemplation of concrete suggestions and steps opens numerous questions.

In particular, when discussing norm 13i (related to supply chain security), States the broad measures such as putting in place, at the national level, transparent and impartial frameworks and mechanisms for supply chain risk management to more narrowly define ones, (e.g. putting in place measures that prohibit the introduction of harmful hidden functions and the exploitation of vulnerabilities in ICT products). The 2021 UN GGE report clarifies that States are primary responsible actors for implementing this norm. However, at the same time, states agreed that the private sector and civil society should assume a relevant role in the process. What can be concrete responsibilities for these stakeholders? The norm does not clarify this issue further.

With regard to norm 13j (related to responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities), the language remains less detailed and specific. The norm promotes a necessity for ‘timely discovery and responsible disclosure and reporting of ICT vulnerabilities’. The norm also mentions that states could consider developing impartial legal frameworks, policies, and programmes on vulnerability handling; develop guidance and incentives, and protect researchers and penetration testers. These measures would find broad support across cybersecurity experts, users, and other stakeholders; however, details are critical – what do ‘impartial legal frameworks’ mean? How will states protect researchers and penetration testers? And what would ‘responsible reporting’ entail? To whom should vulnerabilities be reported to ensure responsible reporting? The norm does not clarify this either.

Discussions with the Geneva Dialogue experts have highlighted that these questions are just as important and on the minds of stakeholders. They have raised additional concerns, such as how to tackle the current geopolitical challenges arising from technological competition between countries and the different rules and regulations in this field. These challenges and risks of conflicting rules and laws in this field across countries can present hurdles for researchers and industry players trying to collaborate across borders to put these norms into action.

The role of governments in the implementation of these norms raised another concern, especially in regards to the states who have advanced cyber capabilities to stockpile vulnerabilities for their cyber offensive and defensive programs. How to build trust between relevant non-state stakeholders and governments to implement these norms and encourage responsible vulnerability disclosure? How to facilitate information exchange to implement these norms between states and relevant non-state stakeholders, as well as between different states?

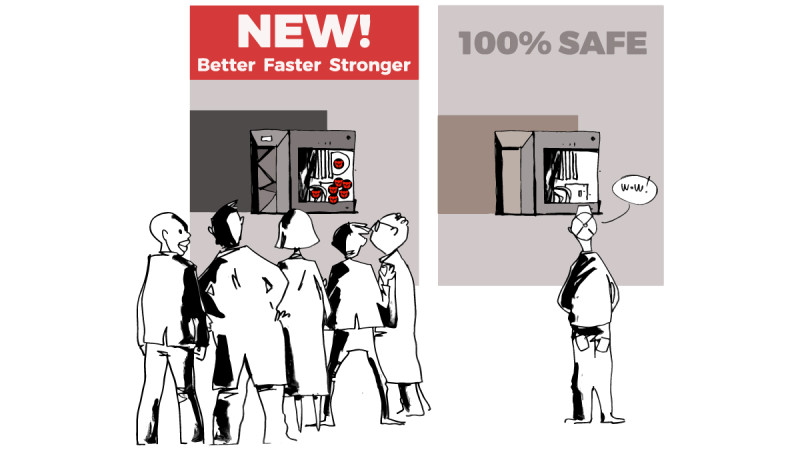

The Geneva Dialogue experts have also expressed concerns about the implementation of the norm 13i on supply chain security. In particular, it has been noted that the ICT supply chains now involve multiple stakeholders, and that no single entity has complete control over them. The complexity of these supply chains, with various participants and cross-border data flows, makes achieving optimal security challenging. Each organisation makes security decisions based on its resources and capabilities, which may not align with the security needs of others. The absence of universally accepted methods for conducting evidence-based security assessments in supply chain security poses challenges for organisations of different sizes. They must make security choices and decide which digital products and suppliers can be trusted. All these decisions often have an immediate impact on the security of customers and users. In this context, the Geneva Dialogue experts stressed the need for globally accepted rules and standards for supply chain security, promoting security by design and default in digital products. However, is it possible to develop such rules today, and is there an appropriate international platform for facilitating these discussions?

While norms set expectations, translating them into practical actions is of the essence. The Geneva Dialogue experts supported translating the norms as non-binding diplomatic agreements into more tangible processes, policies, and regulations. The key questions are how to develop such policies and regulations, and where to establish them. What should be the fundamental principles guiding the creation of such policies and regulations to effectively implement the essence of the norms?

With many open questions, the consultations with the Geneva Dialogue experts showed that relevant non-state stakeholders support the norms negotiated by states: if properly implemented, they can help significantly increase the security and stability in cyberspace. But the ‘devil is in the details’ and the key caveats are about ‘if’ and ‘properly implemented’ – what would this mean in practice?

With the Geneva Manual, we launch a global conversation on how the norms implementation for the security of cyberspace can become a reality or, where it is already a reality, what can be improved. Based on the idea that achieving effective cybersecurity requires continuous cooperation and commitment from all involved parties, we have outlined suggestions as to ‘who should do what.’ With the help of our story (inspired by real events), we explore different roles within various stakeholder groups and delve into what each role can include, and could contribute to. This involves understanding the expectations, motivations, incentives, and challenges faced by these groups. Through the regular discussions with the Geneva Dialogue experts, we also discovered some good practices that can inspire others in the international community to play their part in promoting cyber-stability.

4.2 Implementation of the two norms: Roles and responsibilities to achieve cyber-stability

Remember our story? Who should do what to prevent such incidents from happening again?

How will the national policy maker or a cybersecurity agency work to ensure security and safety for users, while preventing security risks from becoming worse?

As an ICT vendor or manufacturer, what steps would you take to keep your customers – especially those in critical sectors – confident and trusting your services while avoiding unnecessary government scrutiny? What challenges may you face in doing so?

Can the researchers and academics do anything to analyse emerging risks and good and bad practices, or increase knowledge and understanding of the technical and social challenges?

As a customer (e.g. an organisation/company) of the digital product/ICTs which could be affected by a vulnerability, what measures would you adopt to minimise the risks for your operations and negative impact, if any, for your stakeholders and users? What obstacles may you come across in this process?

What can civil society organisations (e.g. consumer protection organisations and advocacy groups) do to improve the overall awareness and impact the policy environment that ensures prevention, protects citizens, and holds parties accountable for mistakes?

The questions above are intentionally simple. We wish to focus on one crucial aspect: if there is an urgent risk in the digital world, who should take the lead in fixing it? Is it the person or organisation or institution with technical expertise or political influence, or the one using the technology?

We often say that cybersecurity is a team effort, but how can we ensure that such a ‘team’ works together effectively? To address this, we collected the views of the Geneva Dialogue experts: these multistakeholder inputs helped us analyse where roles start and end, which drivers are needed to incentivise responsible behaviour across relevant non-state stakeholders, and which challenges remain unsolved, therefore requiring further attention of the international community.

If you were the owner of an open-source tool where the vulnerability had been discovered, what actions would you take to minimise the security risks? What difficulties may you encounter in taking such actions?

As a customer and user of digital products, what would you expect from your suppliers? What would motivate you to keep trusting them?

Do researchers – when discovering the vulnerability – always have to coordinate actions with vendors? Authorities? To whom would the reporting of vulnerabilities be considered as ‘responsible’ following the norm 13j?

Can (and should?) cybersecurity researchers independently mitigate the exploitation of the vulnerability without notifying the manufacturer? Or national authorities?

It is important to note that the Geneva Dialogue experts have recognised that each of the listed stakeholders has many sub-groups that might have additional specific roles and responsibilities. For instance, manufacturers include producers of software and hardware, as well as service operators of the cloud or telecommunication infrastructure, while civil society includes advocacy groups, grassroot organisations, think-tank and educational institutions. In addition, there may be a need to elaborate on roles of responsibilities of additional stakeholder groups, such as the standardisation community. Such discussion may be part of the future work of the Geneva Dialogue, towards the next edition of the Geneva Manual.

Separately, the Geneva Dialogue experts have discussed expectations from states and regional organisations and highlighted their role in coordinating efforts with other states to ensure the ICT supply chain security (given ICT supply chains are global and cross-border) as well as in addressing security issues in digital products with efficient legal framework and policies:

- Codifying the norms and promoting responsible behaviour norms should be translated into clear regulatory expectations, though this can be very challenging given the complex nature of ICT supply chains. The clear interoperable security criteria for testing and security assessments are needed to address both technical and political concerns these days

- However, even if such regulatory frameworks emerge, the challenge is to ensure the adoption of cybersecurity recommendations across organisations, especially across small and medium companies. While guidelines may be published to mitigate supply chain vulnerabilities and reduce risks, it remains unclear how to ensure that organisations actually follow these recommendations

- In the context of OSS, government bodies could step in coordinating efforts between manufacturers, open-source community, and other relevant parties, sharing information, and leveraging international collaborations to address cybersecurity threats and support their respective countries in times of crisis

- The national governments’ ability to communicate and collaborate with other states is considered crucial in effectively addressing cybersecurity challenges, as well

- States are also expected to encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities, recognise their exploitation as a threat, increase transparency about stockpiling of ICT vulnerabilities (such as through vulnerability equities processes, VEP), and limit commercial exploitation of ICT vulnerabilities 21OSCE Confidence-building measure (CBMs) on #16: “Participating States will, on a voluntary basis, encourage responsible reporting of vulnerabilities affecting the security of and in the use of ICTs and share associated information on available remedies to such vulnerabilities, including with relevant segments of the ICT business and industry, with the goal of increasing co-operation and transparency within the OSCE region. OSCE participating States agree that such information exchange, when occurring between States, should use appropriately authorized and protected communication channels, including the contact points designated in line with CBM 8 of Permanent Council Decision No. 1106, with a view to avoiding duplication”. – https://dig.watch/resource/confidence-building-measures-reduce-risks-conflict-stremming-ict

GCSC Norm #3 to Avoid Tampering: “[…] the norm prohibits tampering with a product or service line, which puts the stability of cyberspace at risk. This norm would not prohibit targeted state action that poses little risk to the overall stability of cyberspace; for example, the targeted interception and tampering of a limited number of end-user devices in order to facilitate military espionage or criminal investigations.” – https://hcss.nl/gcsc-norms/

5Messages and next steps: Areas requiring further discussion and action

The Geneva Manual builds on the principle of ‘shared responsibility’ and, as the Geneva Dialogue, highlights the importance of multistakeholder participation in the implementation of agreed cyber norms and, thus, in ensuring security and stability in cyberspace. Success in reducing risks in cyberspace relies on an effective multistakeholder participation. However, it also comes with several challenges: power imbalances (e.g. between larger private companies and individual independent OSS developers), communication barriers (e.g. difference in technical expertise between cybersecurity researchers and academia), resource disparities, lack of trust, changing dynamics (i.e. changes in leadership and organisational structures) and others.

The inaugural edition of the Geneva Manual reveals numerous areas where relevant non-state stakeholders have different views, but also where they come to agreement with each other and with the norms as a ‘product’ of inter-state diplomatic agreements and views. These areas include:

- #Norms and #roles Stakeholders agree with the norms in general and that everyone has a role to play, though the private sector, and especially those who develop digital products, have a bigger role to play

- #Civilsociety Relevant non-state stakeholders from civil society and academia do have a role to play to implement the two norms on ICT supply chain security and responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities. In particular, they are critical in posing challenging questions (e.g., addressing human rights implications resulting from the exploitation of ICT vulnerabilities by private and state actors) and fostering trust among different stakeholders to promote an international dialogue and collaborative approach

- #Norms Translating the two norms into more practical actions, including policies and regulations are of the essence. A neutral and geopolitics-free governance framework is required to globally approach the security of ICT supply chains, responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities, and security of digital products. While this may be an ambitious goal, the Geneva Dialogue experts emphasised the significance of international dialogue across different jurisdictions involving industry, the private sector, independent developers, SMEs, cybersecurity researchers, and technical community members who contribute to responsible vulnerability disclosure

- #Governments Stakeholders do also expect governments to take a lead and set an example by implementing the norms. This would, in particular, include steps to responsible report vulnerabilities and enhance transparency in government disclosure decision processes

- #Regulations Emerging cybersecurity regulations should avoid requirements to mandate reporting of unpatched vulnerabilities to anyone else but to code owner in order to minimise the risks of accessing this information by malicious actors

- #OSS Implementing both norms is impossible without actively involving, and paying attention to, the OSS community. The community-driven open source development is the achievement in the software development industry which enables technological innovation and growth. And while the security of open-source projects is a challenge, there are ways – more creative than regulations – to support OSS contributors to adhere to a more secure code and practices to mitigate vulnerabilities and respond to incidents related to OSS projects

- #Norms Increasing geopolitical polarisation and technological competition between jurisdictions end up with conflicting laws and therefore poses a challenge for relevant non-state stakeholders to implement the norm, specifically norm 13i, and address risks associated with ICT supply chain security

- #Vulnerabilityreporting There is a need for legal reforms that decriminalise vulnerability reporting and provide clear protections for researchers. Establishing supportive legal frameworks to implement the norm, specifically norm 13j, and which focus on encouraging responsible reporting without malicious intent can foster a more welcoming environment for researchers to come forward with their findings

At the same time there are open questions which require future discussion with relevant non-state stakeholders and further iterations of work to expand the views captured in the Geneva Manual. These questions include:

- Is it possible to develop common global rules for ICT supply chain security today? Is there an appropriate international platform for facilitating these discussions?

- How can the implementation of both norms be measured?

- How can we avoid the emergence of regulations mandating the reporting of unpatched ICT vulnerabilities to governments and the risks associated with such reporting?

- How should states protect ethical researchers and incentivise them to responsibly report vulnerabilities to relevant code owners and manufacturers?

- Do citizen customers of digital products have a role and responsibility to play in implementing both norms?

- How can customers and manufacturers of digital products be incentivised to choose cybersecurity along with convenience and innovation?

- How can we enhance private and state actors’ accountability in exploiting ICT vulnerabilities?

- How can civil society and academia help address risks for human rights stemming from the exploitation of ICT vulnerabilities?

- What can industry and governments do to support the OSS community in producing a more secure code while avoiding demotivating OSS development and innovation?

These and other more specific questions will guide the Geneva Dialogue in further work to address the implementation gap in discussion with the relevant non-state stakeholders.

6Recommended resources

- ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise, MITRE ATT&CK®, by MITRE

- Brief on UN OEWG and UN GGE processes at DigWatch

- Cyber Incident Tracer, by CyberPeace Institute

- Cybersecurity 10 Principles, by the Charter of Trust

- EU 5G Security Toolbox, by the European Union

- Geneva Declaration on Targeted Surveillance and Human Rights, initiated by AccessNow, the Government of Catalonia, the private sector, and civil society organisations

- Geneva Dialogue webinars on vulnerabilities in digital products: webinar on risks and impacts of vulnerabilities, and webinar on who can do what about it (2023)

- Geneva Dialogue output report on ‘Security of digital products and services: Reducing vulnerabilities and secure design: Good practices’ (2021)

- Geneva Dialogue comparative analysis on ‘Governance Approaches to the Security of Digital Products’ (2021)

- Geneva Dialogue event reports on ‘Security of digital products and the regulatory environment’ and ‘Security of digital products and international standards’ (2021)

- Geneva Dialogue output report on ‘Security of digital products and services: Reducing vulnerabilities and secure design: Good practices’ (2020)

- GCA Cybersecurity Toolkit For Small Business, by Global Cyber Alliance

- Global Encryption Coalition, by the Center for Democracy and Technology, Global Partners Digital, Mozilla Corporation, Internet Society, and the Internet Freedom Foundation

- ai: a project to implement AI to auto-remediate vulnerabilities in OSS

- Guide for Evaluating OSS, by OpenSFF

- Guidelines and Practices for Multi-Party Vulnerability Coordination and Disclosure (2020), by FIRST

- Hardware Bill of Materials (HBOM), by CycloneDX

- International ‘Secure by Design’ guidance from 18 countries (national authorities), by the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- ISO vulnerability disclosure and handling standards: ISO/IEC 29147 and ISO/IEC 30111

- Norms of the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace

- NIS2 Directive: Directive on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the European Union

- OECD Recommendations on Digital Security Risk Management and High-level principles to enhance the Digital Security of Products

- OECD Recommendations on the Treatment of Digital Security Vulnerabilities (2022)

- OSCE Confidence-Building Measures to reduce the risks of conflict stemming from the use of information and communication technologies (2016)

- OSS Code Scanning, by GitHub

- OSS Guidance on adding a security policy to a repository, by GitHub

- OSS Guidance on the vulnerability reporting process, by Linux Foundation

- OSS Guide to Implementing Implementing a Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure, by GitHub

- OSS Secret Scanning, by GitHub

- OSS Vulnerability Guide, by GitHub

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace: 9 Principles

- Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace: Report on Securing ICT Supply Chains (2021)

- Secret Scanning for OSS, by GitHub

- txt: a proposed standard to allow websites to define security policies, by Google, Facebook, GitHub, the UK government, and other international partners

- Singapore Common Criteria Scheme, by the Singapore Cyber Security Agency (CSA)

- Singapore Cybersecurity Labelling Scheme (CLS), by the Singapore Cyber Security Agency (CSA)

- Singapore Cybersecurity Labelling Scheme (CLS) for Medical Devices, by the Singapore Cyber Security Agency (CSA)

- Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), by the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- SP 800-218 Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF), by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology

- Supply chain security guidance, by the UK National Cyber Security Centre

- Swiss Digital Initiative: an example of the effort to bring ethical principles and values into technologies

- Vulnerability Disclosure Cheat Sheet: Reporting Vulnerabilities, by OWASP

- Vulnerability Exploitability eXchange (VEX) – an overview, by the US National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA)

7Annex

UN GGE 2013 (A/68/98), UN GGE 2015 (A/70/174) and UN GGE 2021 (A/76/135) reports provide the following two norms related to supply chain security and responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities:

Norm 13 (i) “States should take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain so that end users can have confidence in the security of ICT products. States should seek to prevent the proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions.”

- This norm recognizes the need to promote end user confidence and trust in an ICT environment that is open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful. Ensuring the integrity of the ICT supply chain and the security of ICT products, and preventing the proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions are increasingly critical in that regard, as well as to international security, and digital and broader economic development.

- Global ICT supply chains are extensive, increasingly complex and interdependent, and involve many different parties. Reasonable steps to promote openness and ensure the integrity, stability and security of the supply chain can include:

(a) Putting in place at the national level comprehensive, transparent, objective and impartial frameworks and mechanisms for supply chain risk management, consistent with a State’s international obligations. Such frameworks may include risk assessments that take into account a variety of factors, including the benefits and risks of new technologies.

(b) Establishing policies and programmes to objectively promote the adoption of good practices by suppliers and vendors of ICT equipment and systems in order to build international confidence in the integrity and security of ICT products and services, enhance quality and promote choice.

(c) Increased attention in national policy and in dialogue with States and relevant actors at the United Nations and other fora on how to ensure all States can compete and innovate on an equal footing, so as to enable the full realization of ICTs to increase global social and economic development and contribute to the maintenance of international peace and security, while also safeguarding national security and the public interest.

(d) Cooperative measures such as exchanges of good practices at the bilateral, regional and multilateral levels on supply chain risk management; developing and implementing globally interoperable common rules and standards for supply chain security; and other approaches aimed at decreasing supply chain vulnerabilities.

- To prevent the development and proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions, including backdoors, States can consider putting in place at the national level:

(a) Measures to enhance the integrity of the supply chain, including by requiring ICT vendors to incorporate safety and security in the design, development and throughout the lifecycle of ICT products. To this end, States may also consider establishing independent and impartial certification processes.

(b) Legislative and other safeguards that enhance the protection of data and privacy.

(c) Measures that prohibit the introduction of harmful hidden functions and the exploitation of vulnerabilities in ICT products that may compromise the confidentiality, integrity and availability of systems and networks, including in critical infrastructure.

- In addition to the steps and measures outlined above, States should continue to encourage the private sector and civil society to play an appropriate role to improve the security of and in the use of ICTs, including supply chain security for ICT products, and thus contribute to meeting the objectives of this norm.

Norm 13 (j) “States should encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities and share associated information on available remedies to such vulnerabilities to limit and possibly eliminate potential threats to ICTs and ICT-dependent infrastructure.”

- This norm reminds States of the importance of ensuring that ICT vulnerabilities are addressed quickly in order to reduce the possibility of exploitation by malicious actors. Timely discovery and responsible disclosure and reporting of ICT vulnerabilities can prevent harmful or threatening practices, increase trust and confidence, and reduce related threats to international security and stability.

- Vulnerability disclosure policies and programmes, as well as related international cooperation, aim to provide a reliable and consistent process to routinize such disclosures. A coordinated vulnerability disclosure process can minimize the harm to society posed by vulnerable products and systematize the reporting of ICT A/76/135 16/26 21-04030 vulnerabilities and requests for assistance between countries and emergency response teams. Such processes should be consistent with domestic legislation.

- At the national, regional and international level, States could consider putting in place impartial legal frameworks, policies and programmes to guide decision – making on the handling of ICT vulnerabilities and curb their commercial distribution as a means to protect against any misuse that may pose a risk to international peace and security or human rights and fundamental freedoms. States could also consider putting in place legal protections for researchers and penetration testers.

- In addition, and in consultation with relevant industry and other ICT security actors, States can develop guidance and incentives, consistent with relevant international technical standards, on the responsible reporting and management of vulnerabilities and the respective roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in reporting processes; the types of technical information to be disclosed or publicly shared, including the sharing of technical information on ICT incidents that are severe; and how to handle sensitive data and ensure the security and confidentiality of information.

- The recommendations on confidence-building and international cooperation, assistance and capacity-building of previous GGEs can be particularly helpful for developing a shared understanding of the mechanisms and processes that States can put in place for responsible vulnerability disclosure. States can consider using existing multilateral, regional and sub-regional bodies and other relevant channels and platforms involving different stakeholders to this end.

Further elaboration of these norms can be found in the UN GGE 2021 report (A/76/135).

Subsequently, the final report of the UN OEWG (A/AC.290/2021/CRP.2) in 2019 also provide that, “States, reaffirming General Assembly resolution 70/237 and acknowledging General Assembly resolution 73/27, should: take reasonable steps to ensure the integrity of the supply chain, including through the development of objective cooperative measures, so that end users can have confidence in the security of ICT products; seek to prevent the proliferation of malicious ICT tools and techniques and the use of harmful hidden functions; and encourage the responsible reporting of vulnerabilities” (para 28).

Leave A Comment