What are vulnerabilities?

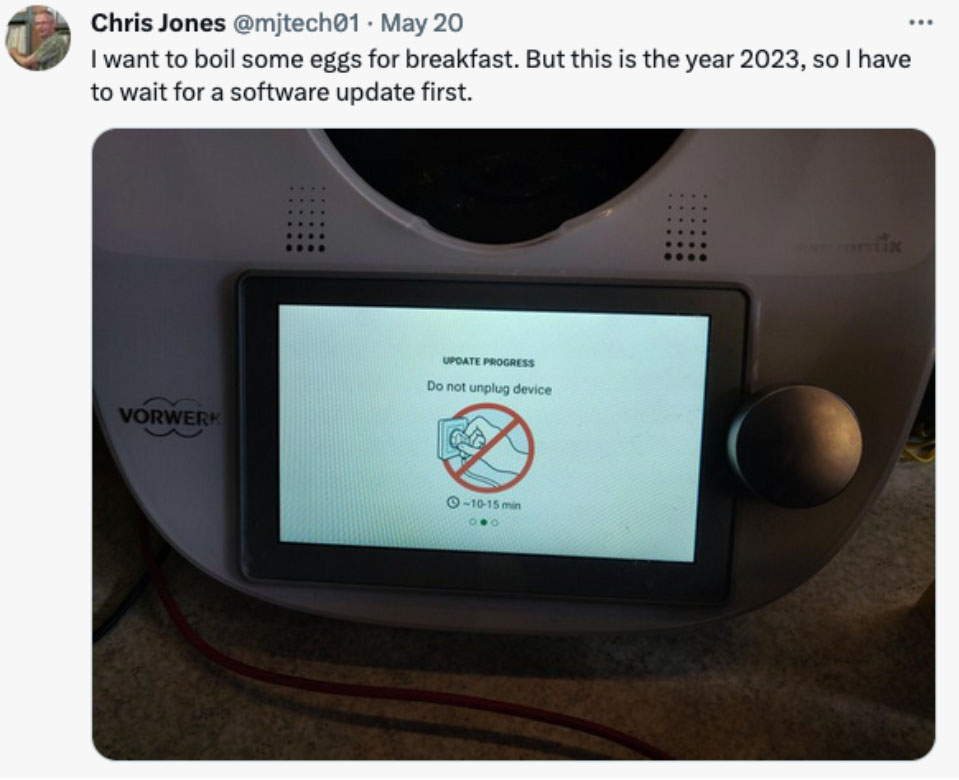

Many of us are probably used to the all too frequent messages like ‘Update in progress, don’t turn off your computer.’ We see this not only on our laptops but also on our mobile phones, game consoles, fridges, cars, lightbulbs, fish tanks, and egg cookers.

Source: Chris Jones on Twitter.

These updates fix bugs (i.e. faults in the software), which today is part of nearly everything moderately complex we use. Some of these faults are merely annoyances, while others can be serious security risks. Think of a dripping tap versus a broken lock on your house.

Faults with security implications are called ‘vulnerabilities’. These can, and likely will, be used by malicious actors, criminals, or states to gain access to affected devices.

Why is this bad?

But is this really a problem? Who would care about an egg boiler? Well, no one really, it only becomes interesting if it can be used as a jumping point to something more interesting. The vulnerable egg boiler will be connected to an internal network, and depending on who operates the egg boiler, this might be big. For example, in 2017, a casino was hacked through a fish tank.

While all these anecdotes seem more amusing than alarming, there are some serious consequences to ponder. In essence, a vulnerability is often the beginning of a quiet devastation attack. Nothing reflects this better than prices which are paid for new vulnerabilities, up to several millions of dollars to access, for example, a mobile phone. These vulnerabilities are then used to create spyware, software designed to spy on victims. Many of these, like the well-known Pegasus software, are then used by rogue actors to spy on people, more often than not activists, journalists, human rights defenders, etc., often with deadly consequences. Or they are used by criminals, such as ransomware gangs, to hack private companies, governments, or hospitals and extort them for millions of dollars.

But it is not only criminals that use vulnerabilities but also states which use them for their intelligence operations or offensive operations. In 2021, China, for example, was accused of exploiting a vulnerability in Microsoft’s popular exchange servers to hack thousands of government organisations. Once the vulnerability became public, criminals and ransomware gangs followed up, creating a near overload of the global incident response community, and it took months to clean up the mess. Vulnerabilities are even difficult if they are no plans for deployment. For example, the NSA stockpiled an exploit, dubbed EternalBlue, against Samba, a popular Microsoft network file-sharing protocol. This exploit got stolen, ended up in public, and was consequently used by an actor deemed connected to Russia in the NotPetya Wiper, which, presumably by accident, brought down the internet, allegedly creating costs of US$10 billion. If this sounds like a bad movie, it’s probably because it’s not a movie plot.

So, in short, no one is safe from vulnerabilities. This creates a distrust in the internet that may prevent people from using it, or cause states to overreact: just imagine if you are responsible for some critical infrastructure, say a nuclear power plant, but you never really know if it is secure.

What can states do?

The problem, in fact, is so grave that the UN General Assembly in 2015 endorsed two so-called norms for responsible state behaviour, agreed upon by the UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE):

- States should encourage responsible reporting of ICT vulnerabilities and should share remedies to these.

- States should take steps to ensure supply chain integrity, and should seek to prevent the proliferation of malicious ICT and the use of harmful hidden functions.

However, states don’t universally implement these two norms. Some states, for example China, require that all vulnerabilities be reported with no clear process of what happens then. Others, such as the USA and the UK, have published a Vulnerability Equities Process (VEP) that describes what they do with vulnerabilities they have exclusive access to. The VEP describes the process by which states decide to disclose a vulnerability and thus have it fixed versus keeping it for their own use. Yet others, such as Switzerland, feel vulnerabilities should always be disclosed and fixed, and help finders to get this achieved. Many states are just silent.

Realistically, an ‘always-disclose’ policy is what we should hope for, but a VEP is what we can expect. Anything else seems irresponsible and not in accordance with the above norms, that all states agreed to in the UN General Assembly.

What can you do?

That of course depends very much on who you are. If you’re a simple user, the least you can do is install security updates when they come out and maybe make sure you understand your risk profile. If, however, you are a state, you might want to take the above two norms to heart and implement them in a responsible manner. If you are a vendor, make sure you can deal with vulnerabilities. The Geneva Dialogue has some handy information that may help you further . Also, FIRST has published Guidelines and Practices for Multi-Party Vulnerability Coordination and Disclosure. The Geneva Dialogue is now building on this expertise to create a Geneva Manual which documents what a given norm implies for different stakeholders.

Conclusion

Vulnerabilities are a destabilising element in cyberspace, undermining the trust of users and states. They can and are abused daily. While states have committed to responsibly dealing with vulnerabilities in 2015, few walk the talk. Depending on your role, you can actually help make things better.